Manitoba Hydro’s keeyask project leaves fish inedible for locals in Makeso Sakahikan (Fox Lake/Gillam).

By Chantal Marie Schromeda and Lawrence Saunders Jr.

As traditional harvesters pack their fishing gear with youth in tow, they prepare for a long commute 50 kms south of Makeso Sakahikan (Fox Lake/Gillam) to harvest and process healthy fish they can bring back and distribute amongst the community.

Harvesters in Makeso Sakahikan travelling to harvest fish. Lawrence Saunders Jr

With high mercury levels in the Nelson and Stephen’s waters due to Manitoba Hydro’s flooding from the reservoir for the hydroelectric keeyask project, the fish are no longer safe to consume.

“This is our new normal for the next 15-20 years,” says traditional harvester Lawrence Saunders. “This is the distance we must travel now just for fish and further.”

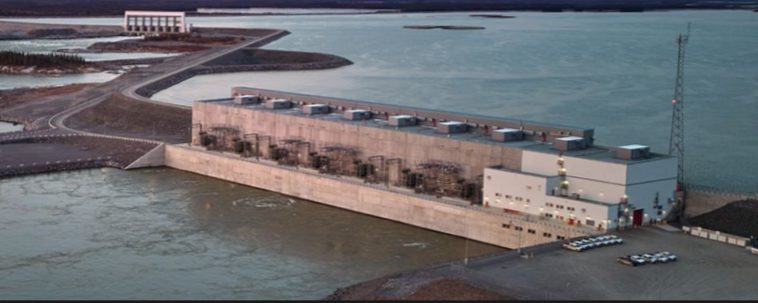

The keeyask project is a 695 megawatt renewable hydroelectric energy generating station near Gull Rapids on Nelson River that will be integrated into Hydro’s electric system for use in Manitoba and for export outside the province, according to the Keeyask Environmental Impact Statement. The project consists of principal, supporting, and permanent structures – a powerhouse and service bay complex, dams, dykes, roads, communication tower, work areas, etc. Mercury levels in species such as Lake Whitefish, Northern Pike, and Walleye are expected to increase around two to five times from the 45 sq km of flooded land from the reservoir in Gull and Stephen’s Lake.

The keeyask project. Photo courtesy of Hydro

Long-term flooding of lands following the construction of reservoirs accelerates the conversion of naturally occurring inorganic mercury to methyl-mercury, according to the Manitoba Government. Methyl-mercury is an organic and more toxic form of mercury that accumulates in fish. While methyl-mercury levels eventually decline, it takes 20-35 years to do so.

“The mercury levels are close to doubling from safe eating levels,” says Saunders. “Every lake has mercury but there’s certain levels that are considered safe to consume, and ours in the Stephen’s Lake and Nelson River are way too high right now.”

While there has been debate on safe fish consumption levels, there is a 0.5 ppm (parts per million) consumption guideline set for commercial fishing by Health Canada for the general population. A threshold of 0.2 ppm has also been utilized by Canada as a safe consumption limit for those eating large quantities of fish, according to the Fox Lake Cree Nation’s Environment Evaluation Report. According to the Manitoba Government, the 0.2 ppm threshold also holds for safe methyl-mercury consumption guidelines for the sentitive population – women of childbearing age and children under 12. Mercury concentrations for the keeyask project are expected to exceed the 0.5 ppm recommendations by Health Canada.

According to recent post-impoundment mercury concentration results in Gull Lake provided by Hydro, average mercury concentrations in pickerel and jackfish are 1 ppm. Average 2024 concentrations in Gull Lake whitefish were 0.19 ppm, while mercury concentrations of pickerel and jackfish in Stephen’s Lake were 0.5 ppm.

Total reservoir area of the project. Photo courtesy of Hydro

Harvesters like Saunders are concerned about the community’s health, eating less wild food, having to rely on southern buyers, and needing to travel further to lakes and rivers that don’t flow into the Nelson.

According to Health Canada, methyl-mercury can cause personality changes, tremors, deafness, memory loss, changes in vision, etc. Children are especially vulnerable and could experience a decrease in IQ, delays in walking and talking, blindness, seizures, etc.

And while no one in the community is believed to have been sick from mercury recently, Saunders is hoping it stays that way.

To determine community members’ mercury levels, north and south consultants have been coordinating yearly mercury testing.

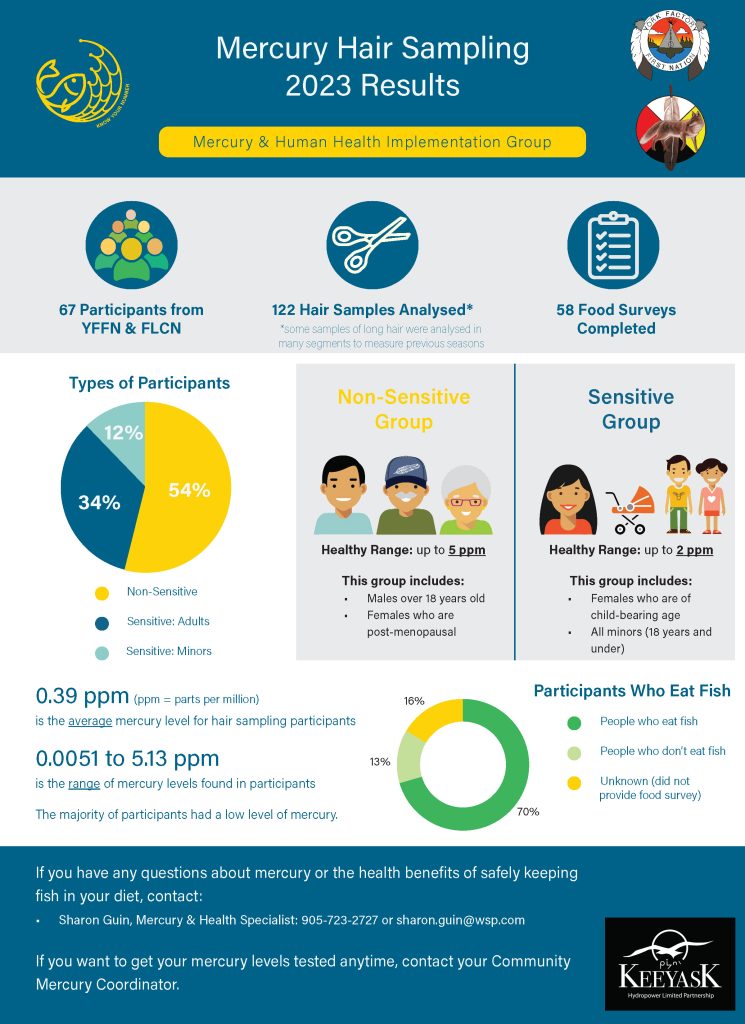

According to 2023 mercury test results provided by Hydro, approximately 67 participants from Kiscewaskahikan (York Factory) and Makeso Sakahikan provided 122 hair samples and 58 food surveys to measure their mercury levels. Of those, 54 per cent were non-sensitive adults (men over 18 and women post-menopause), 34 per cent were sensitive adults (women of child bearing age and all minors), and 12 per cent were sensitive minors. Of the participants, 70 per cent ate fish, 13 per cent did not eat fish, and 16 per cent were unknown (did not provide a food survey). The results range from 0.0051 to 5.13 ppm found in participants. While Hydro states that 0.39 ppm was the average mercury level found in participants, the results do not specify which test group acquired which mercury levels.

Mercury test results. Photo courtesy of Hydro

Hydro states they are working on obtaining more recent mercury test results from the community.

Hydro also provided results for a wild food survey showing most participants do continue to harvest, share, and eat fish from non-keeyask impacted water, with some limited fishing on Stephen’s Lake.

When prompted about efforts Hydro has taken to work in collaboration with the community, Hydro spokesperson, Peter Chura, points to the project’s mercury fact sheet.

“This document speaks to the efforts taken to address potential and expressed concerns,” he says.

The document addresses Hydro’s ongoing mercury tests, the hiring of mercury community coordinators to serve as local information resources about mercury and health, coordinating hair sampling and information sessions with youth, fishing events, and the preparation of Cree-informed communication materials such as a food web poster and calendars, along with the Healthy Food Fish Program.

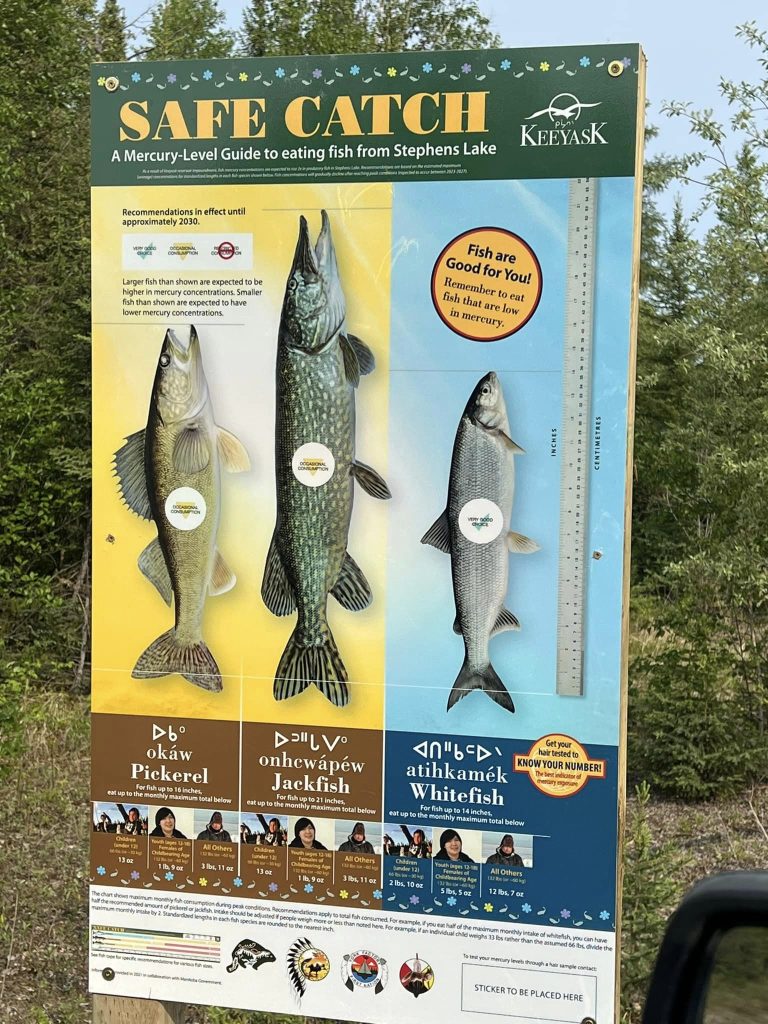

Updated “Safe Catch” signage and government issued public notices were also installed in 2023 at two Stephen’s Lake boat launch locations in the Gillam area, and at upstream and downstream keeyask boat launch areas.

Safe catch sign. Lawrence Saunders Jr

But many people in the community are still unaware of the mercury levels.

“There’s lots of new people moving here and plus, all the contractors fishing all summer,” he says. “There’s signs at the fishing spots but nobody reads them.”

The Healthy Food Fish Program is a part of the Adverse Effects Agreements, which Hydro states they had negotiated with each partner Indigenous community. The program is intended to provide opportunities for the community to continue fishing by paying for the cost of a cabin, dock, ice house, storage shed, and fish cleaning table at Waskaiowaka, Recluse, Pelletier, Myre, and Limestone, according to the Keeyask Environmental Evaluation. While the evaluation shows there are four snow machines and sleds, four boats and motors, and fishing nets available, they must be purchased.

Proper transportation is a necessity to reach healthier waters, and Saunders wants to see a collaboration to meet halfway on coming up with an accessible solution.

“I’d like to see a collaboration where Hydro and Fox Lake meet halfways on making a positive way for us to get fresh fish all year round from the southern areas until our waters are healthy again because it’s a main part of our Indigenous diet,” he says. “Our future generation needs to know our ways of life but we can’t teach that part of it right now due to insufficient transportation out on the land to get to the healthier waters.”

Local non-profit Food Matters Manitoba (FMM) helps support community-led food initiatives and has provided harvesters in Makeso Sakahikan with nets, fishing rods for summer and winter, and line. FMM has also supported community fishing events and the building of smokehouses to smoke fish.

“Most of our support goes to rental and fuel costs associated with getting onto the land to places where fish can be harvested,” says Northern Programs Manager, Myles King.

Despite offering transportation support, FMM would need a significant amount of funding to create routine trips to healthier waters, he adds.

“Some funders restrict funding to not be used for fuel or the rental of personal vehicles for this type of work,” he says.

FMM also helps coordinate other ways for the community to access healthy fish. The annual trip to Kinosao Sipi (Norway House) is an opportunity for harvesters and the youth to harvest fish unaffected by Hydro development.

“It’s cost extensive but participants love the experience, and the fish is well received when brought back to the community,” adds King.

Last year in March, harvesters from Kinosao Sipi, Kisipakamak (Brochet), and Makeso Sakahikan spent two days ice fishing with youth. Over 50 walleye were brought back to the community to hand out and have a fish fry.

Community Project Coordinator and harvester Myron Cook at the recent annual fishing trip in Kinosao Sipi. FMM

The relationship between Hydro and the community has been one of exploitation since Hydro development began in the early 1960s. The keeyask project is seen as an additional development tallied onto decades worth of damage, states the Fox Lake Cree Nation Environment Evaluation Report.

For Leslie Dysart, CEO of the Community Association of South Indian Lake (CASIL) and traditional harvester, mercury concerns in Makeso Sakahikan parallel how his community has been impacted by Hydro.

“We here in the community of O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation (South Indian Lake) have ongoing concerns of mercury levels,” he says.

The community was flooded in the early 1970s as a result of the Churchill Diversion Project, continually experiencing excessive water level fluctuations that can be described as additional flooding annually. The initial flooding and annual fluctuations contribute to added mercury in the food chain, explains Dysart.

The community was and is, a fishing community, and Dysart has heard many concerns over the years that remain unaddressed.

“Both Manitoba and Manitoba Hydro barely acknowledge the ongoing mercury contamination, and do not study or monitor the consumption and damage to the community,” he adds.

With no information programs or resources to inform people, Dysart explains that Canada and the Manitoba Government do not inform the community of health concerns and that there has only been two tests in the community during his lifetime, to date.

“When I was twelve, I was tested and had a high concentration of mercury. I was tested again in my 30s and told it was “normal,” but this leads to many questions and further concerns,” he continues. “I and my family continue to consume fish on a regular basis, perhaps more than the average resident.”

The dangers from high mercury levels have short and long-term consequences on the people, the land, and the wildlife.

“In the short term, this issue can disrupt people’s daily lives by forcing communities to outsource food and resources that were once locally available,” says FMM’s Northern Coordinator, Morgan McCurdy. “It can lead to a loss of land use and increased reliance on expensive goods. If not addressed, the long term effects could be catastrophic.”

Continued exposure to contaminated fish and water from the polluted river can lead to mercury poisoning, which would create a greater need for a more robust and intensive healthcare system, she explains.

It’s important for Hydro to take a transparent approach on lasting impacts and new projects if any progress is going to be made, adds King.

“Hydro has left its impact on the territory, so finding new ways to restore, access, and preserve the land for future generations must be done through honest dialogue,” he says.