How Indigenous non-profit Food Matters Manitoba is helping northern communities heal from the trauma of colonization by building local food systems.

By Chantal Marie Schromeda

Note – The term “Indian” when used to identify Indigenous Peoples may be offensive. The term in this article has been used through direct quotations and/or from historical, legal documents.

For Indigenous Peoples, the impact of colonization and the residential school system has been devastating.

Indigenous families have been affected by alcohol, trauma, and abuse for generations – reflecting colonization’s lasting impact, explains traditional harvester in Kisipakamak (Brochet), Myron Cook.

“It created intergenerational trauma, addictions, culture shock, loss of our culture, language, and religion,” says Cook, Food Matters Manitoba’s (FMM) Community Project Coordinator. “Alcoholism and drug abuse were the cheapest and easiest answers to the traumatic events that happened to our people within these schools.”

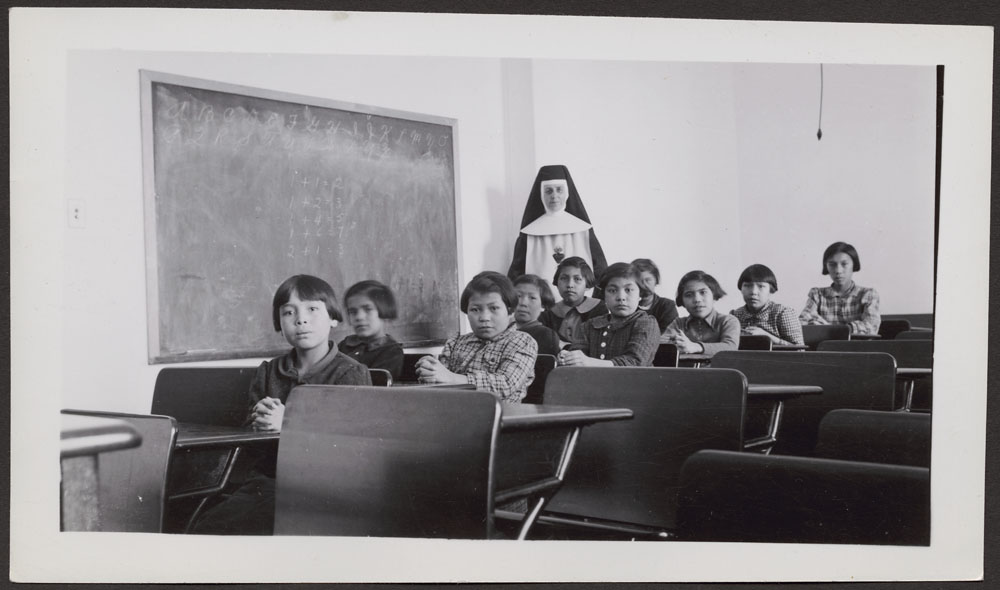

Group of female students [7th from left Josephine Gillis (nee Hamilton), 8th from left Eleanor Halcrow (nee Ross)] and a nun (Sister Antoine) in a classroom at Cross Lake Indian Residential School, Cross Lake, Manitoba, February 1940. Library and Archives Canada/Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds/e011080274

Colonial powers stripped away rights as they sought control and profit.

“Our land and resources were restricted, taken away, and destroyed,” says Cook. “Our resources are restricted and held against us by rules and regulations set by the government. Our land was taken away, colonized, and stripped for uses such as mining, hydro-electric dams, and logging which was forgotten for years without consideration.”

Now, Indigenous communities in the north are receiving payments in an attempt to cover up what was lost, but the compensation is merely a band aid and does not fix colonization’s deep roots, adds Cook.

“It will never compare to what we had,” he says.

Colonization has affected Indigenous peoples’ health, and their overall well-being socially, spiritually, economically, and culturally for generations, according to a 2020 study published in the Journal of Transcultural Nursing. War, widespread massacres, genocide, displacement, forced labour, the forcible removal of children from their parents, residential schools, environmental destruction, unintentional spread of deadly diseases, assimilation, and the attempt at exterminating Indigenous social, cultural, and spiritual practices have all been inflicted by colonial powers towards Indigenous Peoples. The historical trauma and grief has been passed on for generations. But by connecting to culture, harm reduction and meaningful conversations about healing from past trauma can take place. Local food systems in Indigenous communities are vital for the connection to culture – harvesting food from the wild is deeply connected with spirituality, ways of seeing life, language, and links to ancestors – forming the base of ethics and identity, according to the 2009 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ (FAO) Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment Report. Food Matters Manitoba (FMM), an Indigenous non-profit based in Winnipeg, is making strides to heal colonization’s impacts in the north through an approach to food security intertwined with food sovereignty that is actively undoing the impacts of colonization, explains FMM’s Executive Director, Demian Lawrenchuk.

For generations colonization has defined what a food system looks like in Indigenous communities – the support is tailored to include and promote the cultural components of food that have been suppressed by the legacy of colonization, states FMM’s Northern Programs Manager, Myles King.

FMM partners with 13 Indigenous communities in Northern Manitoba and supports capacity building initiatives that build towards enhanced community food systems – tackling food insecurity in the north through community driven change.

By addressing communities’ unique and individual needs, the organization works together with communities to build local food systems and support long-term community led initiatives to reduce food insecurity.

FMM looks to each community’s strengths that can be supported while providing new opportunities they’re looking to add – agriculture, livestock, harvesting resources, medicine and ceremony support, infrastructure support, and harvesting employment. But FMM is doing more than helping support traditional harvesting activities – the organization is creating spaces for, and to support, the long journey of healing from trauma.

“We’re undoing the negative impacts of the residential schools by creating space for people to understand themselves and each other, develop healthy identities, find purpose, and share meaning along a powerful healing journey – creating positive experiences, and opportunities to connect with each other and become positive influences,” says Lawrenchuk.

View of Cross Lake Indian Residential School, Cross Lake, Manitoba, August 1939. Library and Archives Canada/Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds/e011080279

The organization is connecting communities with themselves and each other – creating jobs, mentorship, solid foundations, and capacity building to help facilitate the necessary healing from colonization, explains Lawrenchuk.

The colonization of Indigenous Peoples stemmed from a belief of European Christian superiority- a belief that dates back to the early 1400s.

In the 1400s, the Doctrine of Discovery was a series of formal statements or orders from the Pope called papal bulls.

The Doctrine of Discovery is dubbed the beginning – the foundation of genocide containing ideologies that led to dehumanizing, exploiting, and subjugating Indigenous peoples in the centuries to follow, according to the Assembly of First Nations in a 2018 report.

The papal bulls contributed to colonization throughout the age of discovery as Christian explorers claimed lands for their monarchs who justified their actions based on their belief they were superior.

The Discovery was used as “legal and moral justification for colonial dispossession of sovereign Indigenous Nations, including First Nations in what is now Canada,” states the Assembly of First Nations.

The papal bulls weren’t solidified until 1823, when the U.S. case of Johnson v. McIntosh involving a legal dispute in the U.S. high court between a member of the Piankeshaw Native Americans and a member of the federal government who acquired the same piece of land took place, as previously reported in APTN. The U.S. government asserted sovereignty over territories it claimed – meaning the high court claimed the land Indigenous Peoples were stewarding.

“That includes the ‘Indians’ who were there,” explains Anishinaabe legal expert and former appellate court judge, Harry LaForme, in an interview with APTN. “In other words, they never owned the land. And it was theirs (U.S. government’s) to discover and to claim.”

This ideology trickled up to Canada 60 years later, and manifested into law when Canada’s highest appeal court imported the same principle around the time of the Indian Act’s implementation.

As the centuries progressed, colonial powers needed Indigenous Peoples in North America to accept the Crown as the entity they would need to enter into negotiations with, explains former Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Murray Sinclair, in a press conference.

In 1763, Indigenous Peoples in North America were promised a Bill of Rights by the King of England – the Royal Proclamation. It was intended to be a declaration recognizing the right to exist and the right to be self-governing within Indigenous Peoples’ territories, adds Sinclair.

But the Royal Proclamation defended Indigenous Peoples against nothing, he explains.

“It was not in fact a shield, it was in fact used by the governments of this country, the United States, and England, as a vehicle by means they could then interfere with First Nations – with their territorial rights,” he says. “If you think about what the Royal Proclamation was, it was in fact an assumption of sovereignty over Indian territory by the Crown.”

Indigenous leaders in North America at the time were not engaged in the process of the Proclamation’s creation, he adds.

The Crown needed Indigenous Nations to accept the Royal Proclamation as the basis to their relationship – there was fear amongst the Crown that the Indigenous Nations would drive out the Englishmen if they came together, continues Sinclair.

In 1763, Sir William Johnson invited all of the Indigenous leaders of the Great Lakes area to attend a gathering with the purpose of discussing the Royal Proclamation. It was during this gathering that promises of allyship were made, he explains.

“The historical evidence shows in fact, over 2000 leaders gathered with him at Niagara in 1764, and at that time he had the Royal Proclamation read to them in their language,” says Sinclair. “He promised them through the issuance of those wampum belts – he promised them that the terms of the Royal Proclamation would now become the basis of the relationship.”

Indigenous Peoples had no one other than the Crown they could negotiate a relationship with, states Sinclair.

The Treaty of Paris (1867), while resolving the World War, meant France, Spain, and Portugal agreed through the treaty that they would recognize British sovereignty in North America – leaving Indigenous Peoples with no negotiating options, he adds.

So, the Indigenous Nations promised they would not engage in war with the Crown – thereby recognizing the Crown’s ability to act under the Royal Proclamation with the understanding that the relationship was one of mutual respect, he continues.

But that promise of a mutually respectful relationship, of allyship, was conveniently forgotten.

“By the time of Confederation in Canada in 1867, you never hear about those things (the promises of allyship) happening,” says Sinclair.

The Confederation of Canada was intended for unification of the country, but Confederation disregarded the interests and treaty rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Indigenous Peoples were not invited or represented at the Charlottetown or Quebec Conferences.

These conferences set confederation in motion through the passing of the British North America Act (1867), later renamed the Constitution Act – where the structure of parliament, and the distribution of powers between the federal and provincial governments were decided.

The Constitution Act granted parliament legislative authority over Indigenous Peoples and their lands, as stated in subsection 91 (24) of the Act.

“The Constitution Act was heavily favoured by the white settlers at the time in Canadian society,” says Indigenous physician and Vice President of the University of Manitoba, Catherine Cook, in a public lecture. “Its purpose was really to profit the settlers and at that time, First Nations land became essentially the most valued currency for the new settlers.”

In 1870, the federal government purchased Rupert’s Land (territory that would become Canada) – the Dominion of Canada (Canada’s formal title at Confederation) then extending their influence over Indigenous Peoples living in that region.

This desire for control led the way for the only race-based legislation in the world intended to promote and affect assimilation – the Indian Act in 1876, states Cook.

The Indian Act was developed through separate pieces of colonial legislation – the Gradual Civilization Act in 1857 (intended to assimilate Indigenous Peoples by encouraging enfranchisement) and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act in 1869, which established the elective band council system.

“It (the Indian Act) had profound impact on the health and well-being of First Nations people in this country,” says Cook. “It touched on and impacted in significant ways the culture of First Nations, the traditional practices, the education, the economic development, and control over personal decision – that’s probably the biggest one is the ability to make decisions that affect you as a person.”

The Indian Act gave the federal government jurisdiction over “status Indians” and governed most aspects of their lives – taxation, regulating band control, money management, etc, while also controlling the production, distribution, and the harvesting of traditional foods.

Subsection 71 (1) states, “The Minister may operate farms on reserves and may employ such persons as he considers necessary to instruct Indians in farming and may purchase and distribute without charge pure seed to Indian farmers.” Subsection 71 (2) continues to state the government may apply profits from agriculture in any way he considers fit. The government also had authority over animals, fish, and other game on reserves, as stated in subsection 73 (1).

For traditional harvester and FMM’s Northern partner in Makeso Sakahikan (Fox Lake/Gillam), Lawrence Saunders, regularly bringing the youth onto the land to show them how to harvest for their communities is an act of reclamation of traditional education and culture.

By bringing back those traditional teachings Saunders believes the intergenerational trauma can heal through this line of work – reconnecting with the land and bringing traditional foods back for the people.

Traditional harvester and Northern partner Lawrence Saunders brings youth out fishing. Lawrence Saunders

“Reintroducing the traditional ways of life – the ceremonies, is just the start to the Native life coming back,” he says.

Indigenous youth are deeply impacted by the generational historical trauma they experience caused by colonization.

But by including the youth in the traditional ways of living, substantial generational change happens.

Youth harvester Sidney Castel in Sherridon. Sidney Castel

“Our work centres around youth, as youth are the future,” says FMM’s Northern Coordinator Morgan McCurdy. “Teaching youth how to harvest, garden, and other skills that not only strengthens food security in Northern Manitoba, but provides a produce pass time that builds skills.”

The school garden program in Tataskweyak (Split Lake) and youth harvester employment in Makeso Sakahikan (Fox Lake/Gillam), both supported by FMM, are both examples of FMM’s work in communities that McCurdy believes highlight the education and opportunities youth are receiving.

Part of the school garden in Tataskweyak (Split Lake). Vivian Lin

Youth in the communities are encouraged to try new things, learn from their mentors, and help provide for their community while developing traditional knowledge and skills they can pass along to the younger generations, she explains.

While the cycles of violence and anger have impacted communities across the north, FMM’s work is awakening a nation by undoing the negative impacts of the residential schools through traditional food production – reawakening the human potential within communities, explains Lawrenchuk.

“It’s about breaking cycles of dependency and empowering ourselves together,” he says.

As the son of a residential school survivor, Saunders says he experienced a difficult childhood.

“For me growing up was not the greatest,” he adds. “I was taught a lifestyle that was not mine to keep.”

With the impact of the residential school system weighing heavily on individuals and communities, Saunders explains that Indigenous communities in the north are struggling to cope.

“We’re losing our people to alcohol, drugs, suicides, and people having bad health at young ages,” he says.

The residential school system was slowly integrated as an attempt to assimilate Indigenous populations into Euro-centric values and ways of living by separating children from their families, communities, and culture.

Prior to the mobilization of residential schools in the late 1870s, Indian Day schools were implemented by the federal government.

Students attending Indian Day schools would attend school during the day – being subjected to the same abuse present in the residential schools and then return home to their families in the evening.

Once residential schools were mobilized, for more than 150 years more than 150, 000 Indigenous, Inuit, and Métis children were taken from their families and communities to attend residential schools, according to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR).

The first residential school opened in 1831 and by 1920, the Indian Act made attendance at residential schools mandatory for Treaty-status children between the ages of 7 and 15 years old.

The NCTR characterized the residential schools as cultural genocide, as the students suffered physical, sexual, mental, and spiritual abuse.

As the residential schools were being phased out, the federal government’s efforts of assimilating Indigenous children into Euro-centric society continued with the “Sixties Scoop,” according to the Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants (OCASI).

The “Sixties Scoop” involved social workers who worked in a Euro-centric value system – placing Indigenous children into care without consent.

With provinces having authority over Indigenous child welfare after amendments were made to the Indian Act, the number of Indigenous children in the child welfare system was over 50 times more by the mid 1960s in some provinces than the early 1950s.

The loss of culture, denial of opportunities, and reserve systems are just a few direct results continuing to affect Indigenous communities in the north as a result of colonial efforts, explains McCurdy.

But FMM’s work is sparking real community change in many of the Northern communities the organization partners with.

“Whether it’s a new gardener looking for support after seeing a neighbour growing or a new youth looking to go out on the land, every year more community members reach out interested in the changes happening within their communities and wanting to join in,” says King.

Despite being a small organization working with a small fraction of communities and populations within the communities, FMM has had concrete success in helping to nurture communities’ growth.

“We’re doing the best we can to do our part and we’re having great success – planting the seeds and nurturing communities’ growth,” says Lawrenchuk.

FMM’s Northern partner and traditional harvester in Kinosao Sipi (Norway House), Lester Balfour, often brings the youth in the community out onto the land to show them how to harvest traditional foods for the community.

Youth help to set nets for the community in Kinosao Sipi (Norway House). Lester Balfour

Balfour has seen community members getting involved with harvesting – gardening, fishing, and tending to the chicken coops, while spending quality time with family reclaiming those traditional values and stewarding the land.

Stewarding the land is a right, and Indigenous Peoples granted rights to settlers through treaties to be able to live on this land – sharing in the legal order that Indigenous Peoples had been stewarding for many thousands of years, explains Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law at the University of Victoria, John Burrows, in a public lecture.

Between 1871 and 1921, a series of treaties were negotiated. Treaties 1 and 2 were the first of 11 treaties negotiated between 1871 and 1921 – both signed in Manitoba. During 1871, Treaty 1 was signed between Canada, the Anishinabek, and the Swampy Cree of southern Manitoba. Treaty 2 was signed a few weeks later in 1871 between Canada and the Anishinaabe of southern Manitoba.

From an Indigenous perspective, this agreement of a treaty meant the maintaining of good relationships, explains Burrows.

“Treaties are kind of an origin story because they talk about how Canada was formed as Indigenous Peoples gave permission in many parts of this country for settlers to be able to live on the land,” he says.

The government’s intent through signing these treaties was to facilitate the West’s settlement and the assimilation of Indigenous Peoples, while Indigenous Peoples sought to protect their traditional lands and livelihoods through signing.

These treaties have contributed to an ongoing legacy of unresolved issues.

But Lawrenchuk states the way out of this negative cycle is for communities to take back control and get back out onto the land.

“We need to get back out to the bush, back to the place that has given us life,” he says. “So, that answer is to get back to our ways, to find our culture, and to completely uncover our culture because that is what’s going to lead us back to living that good life.”

Myron Cook and fellow harvester out on the land harvesting geese. Myron Cook

Community Project Coordinator, Cook, believes FMM’s programs are doing just that.

“Step by step our program advocates for our traditional ways within the community, which includes hunting, fishing, medicine, ceremonies, art, and history of our ancestors,” says Cook. “With everything that has happened to our people we will stand strong and create programs like ours to reconcile, revitalize, and rebuild our culture.”

FMM’s partnerships in communities are centred around trust and respect – drawing on the strength, experience, knowledge, and traditions of Indigenous Peoples.

“There is a lot to be said about the strength and depth of our support – our consistent, adaptable and reliable support that is continuously evolving as we grow with our community partners,” says Lawrenchuk.

Despite all of the atrocities that have occurred in Indigenous communities, Northern partners are confident that with FMM’s work, communities will persevere and rebuild again.

“It may take a generation or two to regain our lives that the colonizers tried taking from us but we will strive again one day,” says Saunders.

Lawrence Saunders out on the land with family. Lawrence Saunders