Local Indigenous non-profit tackles food insecurity in Northern Indigenous Communities in Manitoba through community driven change.

By Chantal Marie Schromeda

Remote areas in Northern Manitoba often experience a constant struggle to acquire the bare necessities they need to survive.

It wasn’t always like this though, explains Executive Director of Food Matters Manitoba (FMM), Demian Lawrenchuk.

“For thousands of years our people thrived,” he says.

Traditional harvester Lawrence Saunders and his son fishing. Demian Lawrenchuk

Northern communities were at the centre of bountiful resources. “We had everything that we needed,” he says. “My grandma, when she grew up, the only thing she bought from the store was flour and sugar – they were independent, fully self sustaining people.”

When Lawrenchuk’s grandmother was six years old, she was kidnapped by Canada and taken into the residential school system – colonial powers and the implementation of colonial policies is when everything changed.

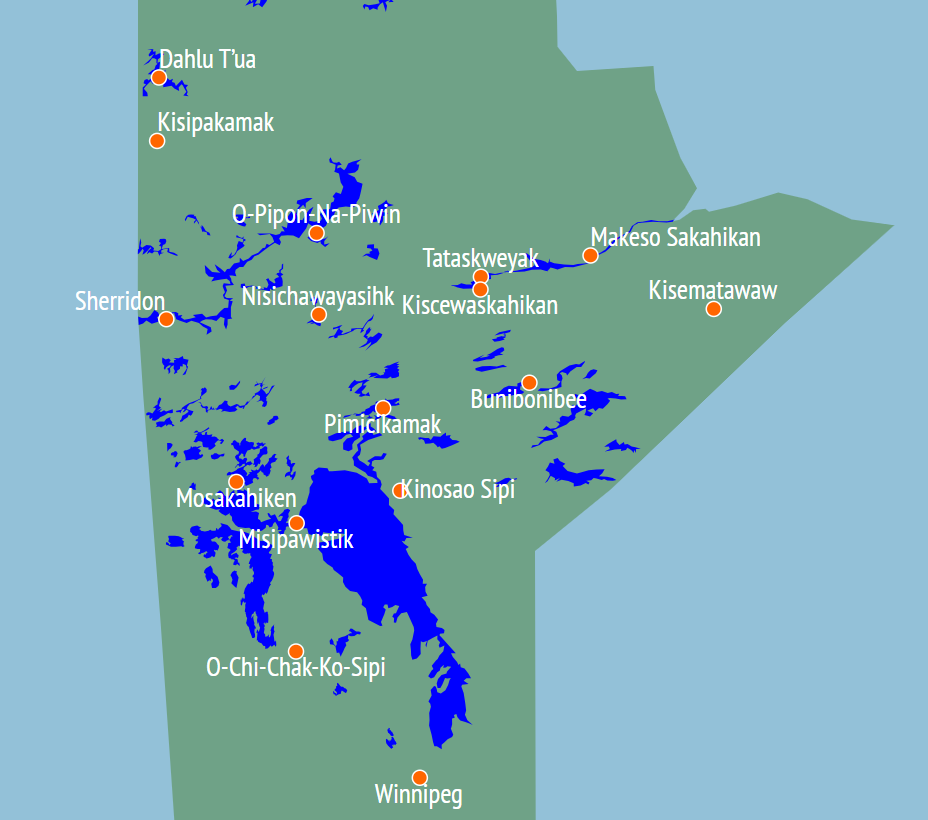

Indigenous peoples disproportionately face much higher risks of food insecurity – the legacy of colonial policies, climate change, environmental dispossession and contamination, and socioeconomic inequities all play a role. With holistic government initiatives to help target Northern food insecurity lacking, Indigenous non-profit in Manitoba, Food Matters Manitoba (FMM), is paving the way forward with a holistic approach to spark real change to Northern food sovereignty. The organization partners with 13 Indigenous communities in Northern Manitoba and supports capacity building initiatives that build towards enhanced community food systems.

Map of Food Matters Manitoba’s partner communities in Manitoba. Food Matters Manitoba

FMM’s Northern Programs Manager, Myles King, explains that the organization looks at each community’s strengths that can be supported while also providing new opportunities that communities are looking to add.

The Northern communities are in the driver’s seat. “All of this has to be community-led,” he says. “A program or project will not endure if it doesn’t align with the vision and will of the community we’re supporting.”

FMM’s support varies depending on what best suits the community.

For example, in Kinosao Sipi (Norway House), FMM sends soil and seeds to Northern partners so they may cultivate annual vegetable crops and berry plants at their local community garden club. In Kisematawaw (Shamattawa), FMM supported the development of two chicken coops so the community may raise chickens as an additional food source.

Growing vegetables for the community in Kinosao Sipi (Norway House). Lester Balfour

Myron Cook, FMM’s Community Project Coordinator and traditional harvester in Kisipakamak (Brochet), explains FMM is making a real and tangible difference up North. “We help the less fortunate,” he says. “We hunt for them, we fish for them, our traditional way.”

There is a large focus with FMM’s work on engaging the youth in the communities. Cook mentors the youth in the North – showing them the traditional ways, providing the opportunity for the youth to connect with their ancestral ties. “Food Matters opens a lot of doors for the youth,” he says.

Cook learnt his harvesting skills from his father, a devoted community member and traditional harvester. “I learnt from my father when I was of age how to hunt and fish – the best fish, the biggest fish, the best part of the meat,” he says.

Myron Cook’s father accompanying him on a caribou hunt. Myron Cook

Now, with the work he does for FMM, Cook is able to pass along the knowledge his father taught him.

“I get to teach the younger children, my nieces and nephews, all around the less fortunate,” he says. “They get that food and the teachings, our traditional way of doing it, nothing goes to waste.”

Myron Cook’s niece harvesting for the community on a harvesting trip. Myron Cook

King explains that with youth engagement, the sparks and strengths of Indigenous food systems can live on for generations.

Youth engagement is a key component of passing along traditional Indigenous food systems.

Traditional Indigenous food systems have struggled to be passed onto new generations – residential schools, the pollution of Indigenous traditional lands, and the ongoing effects of colonialism all contribute to a lack of interest and knowledge in the traditional ways of living, states the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) 2018 Food Policy report.

FMM’s Community Project Coordinator, Lawrence Saunders in Makeso Sakahikan (Fox Lake/Gillam), is the son of a residential school survivor. He adds that there’s been disinterest in the traditional ways of life, like harvesting natural food, as a result of colonization and the residential school system.

“There’s tons and tons of trauma, and I’m just one of the many,” he says.

Lawrence Saunders (left) taking the youth out fishing in Makeso Sakahikan (Fox Lake/Gillam). Lawrence Saunders

In 1883, the Canadian Government funded three residential schools, relying on the churches to provide teachers, states the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation’s Independent Assessment Process Report. The schools were based on the assumption that Indigenous culture and spiritual beliefs were inferior to Euro-centric culture and beliefs.

By 1900, 61 schools were operating in all provinces except for New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. This number eventually grew to 140 operating schools.

Students suffered physical, mental, spiritual, and sexual abuse. They were forced to perform labour, lacked proper nutrition, and were exposed to diseases due to poor sanitation standards. Their relationship with food and the land undoubtedly changed.

In order for governments to truly address the root of Northern food insecurity and tackle it on a large scale nationwide, Gordon Walker, traditional harvester and Northern partner in Kinosao Sipi (Norway House), says there needs to be accountability, honesty, and reconciliation.

For too many generations people have been lied to on both sides, he adds.

Gordon Walker in Kinosao Sipi (Norway House) preparing fish for the community. Lester Balfour

“It’s all about an understanding,” he says. “It’s about a truth and reconciliation.”

When Walker was growing up, everyone had a farm or a garden. People tended to their nutritious foods as they grew and blossomed in abundance across the North, cultivating their relationship to the land – but colonial powers saw an opportunity for profit.

“Back in the day when I was young, I would see these gardens all over the place, but somebody came in there at that time,” he says. “They hired a scientist to say the soil is no good up here – they wanted to make money, they wanted for us to buy from the store.”

Walker explains that it soon became law on the reserves for people to not grow their own food, and colonial policies created a dependence on store goods that are often processed and outrageously priced.

Frozen food prices at the local grocer in Kisipakamak (Brochet). Myron Cook

While current government data for food costs in the North is lacking, the most recent statistics from 2011 show the average cost to fill a basket of food in the North for a family of four for the week is $419.11. In comparison, Dalhousie Canada’s Food Price Report of the same year shows the average weekly cost of a basket of food for four outside of the North is roughly $267.00 a week.

The isolation in Northern communities coupled with the lack of shopping options and high costs poses a real problem – especially for people in the community that don’t have the means to go hunting.

Cook explains that people in Northern communities, especially the less fortunate, are really struggling. “Some don’t have skidoos, boats, and some can’t hunt off the land for themselves,” he says.

In Kisipakamak, Cook says if community members want to shop at the store, they have one option – The Northern Store. “The prices at the store are very expensive,” he says. “The things that are the most expensive are the healthy foods – the berries, the vegetables, the stuff that shouldn’t be expensive because it comes from the earth.”

Price of fresh produce in Kisipakamak (Brochet). Myron Cook

Cook believes getting back to the traditional ways of harvesting the land, caring for one another, and sharing, is vital for Northern communities to combat the food crisis.

When he travels to different nations on his hunts in the far North, Cook says there are times when he runs into other hunters who have nothing to bring back to feed their communities and their families.

“(This one time) I killed enough caribou to fill my toboggan and those other three hunters, they didn’t have anything,” he says. “So, I’d give them one each so they’d have enough to go home with, at least something.”

Myron Cook and crew on one of his caribou hunts. John Halkett

Cook explains that everyone must work together as one in the food systems, that is the traditional way. He adds that it’s vital to harvest food off the land and show each other kindness by sharing amongst the community – that is the way forward.

“That’s very important for our people to get back to the old way,” he says. “Our ancestors have been doing it for thousands of years, we need to bring that sustainability back.”

The cycle of sustainability was broken as a result of colonial powers, explains Lawrenchuk. “The situation that we’re in today – that cycle was broken, it was violently broken,” he says. “When you think about our communities you think about a lot of that negativity.”

While there’s a long way to go for Northern food sovereignty, FMM is helping to lead the way towards real and substantial change.

“Through this work (with Food Matters Manitoba), we’re finding a way to rekindle that spirit in us, to bring back that community cohesion, to unlock the potential of the North so we can stand up together as a province, and set the example for the rest of the country and move forward together with prosperity,” says Lawrenchuk.